Chapter three contains what is probably one of the best-known stories from the Bible. The Babylonian emperor makes a giant idol (which, by the way, has external attestation — Herodotus!) and demands that all of his subjects worship it. The Jews, of course, refuse. Three young representatives of the Jewish people demonstate their God’s superiority and keep the people safe by surviving the flaming furnace. Okay, it’s not terribly hard to figure out what that’s about. It’s also not terrible difficult to figure out why someone living under Seleucid rule would want to tell a story like that, so let’s focus elsewhere.

Look at the structure of the story. Pay attention to the repetition. Notice the nice story arc and the triumphant ending. It’s a wonderful folktale. The kind of thing that wants to be told around a fireplace in the evenings. It communicates cultural and religious values in a suspenseful and entertaining way. Let yourself enjoy the story.

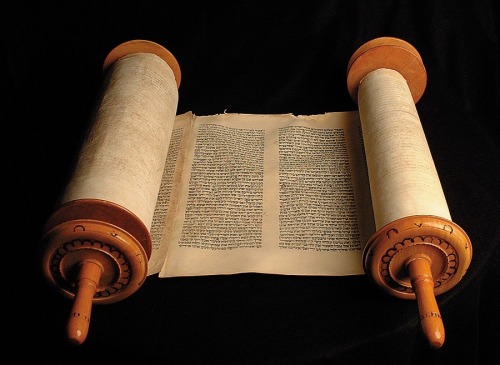

In the Septuagint — and, therefore, in Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Bibles — verse 23 is followed by “The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews.” You can find it in Protestant study Bibles in the Apocryphal section. In case you have trouble finding it, it’s right after the “Letter of Jeremiah.” (You’re welcome!)

In chapter four we encounter another dream. If you recall the dream from chapter two, then the sequence of the story here is predictable. The king dreams; his court magicians can make no sense of it; Daniel proves again the superiority of his God by interpreting the dream. In the first dream, the bad news for the king was that eventually lesser empires would overtake his own. In this case the bad news is more immediate and more personal. The king will go mad and be driven from his kingdom, though he will later return. There is some external attestation for this event, but for a later emperor, not Nebuchadnezzar. There was an emporor named Nabonidus who left Babylon for several years. No explanation for his absence is offered in Babylonian records. A Qumran scroll, however, reports that in Jewish traditions Nabonidus was cured by a Jewish exorcist.

Chapter five tells us the story of the writing on the wall. The king in this part of the story is Belshazzar, who ruled as regent during Nabonidus’s unexplained absence. Belshazzar, having had too much to drink, defiles the Temple vessels that had been brought from Jerusalem when the Temple was razed. Normally the Babylonians would have brought the gods themselves from the peoples they had conquered. This was easy enough to do because the gods are portable. You just bring their statues to your own temple. But the Jewish God was not so easy to move. The Jews didn’t have a statue of their God, and God’s throne — the ark of the covenant — had gone missing. This left the Babylonians with nothing left to claim except the holy vessels used by the priests. Belshazzar had these vessels brought to his banquet where he and his courtiers drank from them. As soon as they did this…(drumroll please)…the writing was on the wall. You know how the story is going to go, right? He brings in his court magicians, but they were good for nothing. Who could possibly help him interpret this strange writing? Daniel! And again, Daniel delivers bad news: your days are numbered; you have been found wanting; your kindgom will be divided. Has anyone noticed that Daniel never brings good news and that he keeps getting rewarded for it? Notice, too, the repetition. The story is easy to remember, predictable, and easy to tell. It’s a perfect folktale.